50. El Mariachi (1992), d. Robert Rodriguez

Robert Rodriguez may be a household name, but back in 1992 he was an impoverished would-be filmmaker who raised $3,000 of the film’s $7,000 shooting budget as a volunteer for experimental drug testing. Shot on the streets of Coahuila, Mexico without storyboards (Rodriguez had no crew to show them to), equipment (sound was record with a tape recorder while most of the ‘guns’ were water pistols) and quite often actors (many of the smaller roles were simply passers by), El Mariachi is guerilla filmmaking at its most inventive. An action movie filmed for the price of a second hand Ford Fiesta – Michael Bay, you have much to learn.

49. Run Lola Run (1998, Ger.), d. Tom Tykwer

Brilliantly high concept, effortlessly executed by director Tom Tykwer and kept at breakneck speed by leading lady Franka Potente, this is one of the very best reasons to bury England’s traditional enmity with the Germans. The story follows three attempts, largely in real time, by Lola (Potente) to get the 100,000 deutschmarks needed to save her boyfriend’s life. Tykwer basically riffs on the same concept three times, ratcheting up the tension and building up the pace with each attempt as the flame-haired Lola uses increasingly inventive means of getting ahead. An object lesson in how to shoot at speed, this smashes the stereotype of the talky, heavy European indie.

48. Cube (1997, Can.), d. Vincenzo Natali

Cube is proof – if proof were needed – that you only need simple concept to make an arresting, interesting film. Taking a small group of people, a confined space and a heavy dose of sinister mystery, Vincenzo Natali probes the darker reaches of human nature, placing his unwitting characters in the ultimate prison: a network of revolving chambers interspersed with intricate (and oft-fatal) traps. Cube was shot in one-and-a-half 14′ by 14′ chambers and the director blagged free visual effects from a Toronto-based company keen to show their support for domestic movie making. The result is a tense and often terrifying tale, that outshines and outscares any number of budget-heavy, studio horrors.

47. Blood Feast (1963), d. Herschell Gordon Lewis

Without Herschell Gordon Lewis’ low budget gore-fest, there would be no Halloween, no Evil Dead et al, and basically half of the ’80s video industry would be missing. This no-budget effort was the birth of splatter. In fact, it’s fair to say that with his entrail packed (however loosely) exploitationer, marketing guru Lewis opened the abattoir doors for ‘meat content’ in films generally – and that includes the likes of ear severing, and faces melting before the wrath of God. Even if you leave the gore aside, the film raked in $4 million from a budget of $24,500. Impressive by any studio outsider’s standards.

46. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), d. Tobe Hooper

With its air of eerie verisimilitude, Tobe Hooper’s chilling horror stands light years apart from the other film based on the gory exploits of the real-life serial killer, Ed Gein. Shot for around $140,000, with money allegedly re-routed from the success of runaway porn hit, Deep Throat, it’sChainsaw‘s dead-eyed, almost cinema verite approach that truly unnerves. The dinner scene, where Marilyn Burns comes dangerously close to having her head smashed in with a hammer, is the most memorable example of Hooper’s edgy approach – something he would never capture again in a career that has since gone spectacularly off the rails.

45. Mad Max (1979, Aus.), d. George Miller

Australians love their cars – something Dr. George Miller was well aware of when he changed careers from physician to filmmaker. Not letting a paltry budget of $400,000 phase him, he fused the cult American sci-fi flick A Boy And His Dog with his own penchant for seeing muscle cars and road bikes moving fast and coming to a scattered end. Acknowledging a massive thirst for automotive action and raking in more than $100 million, it spawned one superior sequel (still one of the greatest ‘real’ action films), which in turn led to dozens of cheap ‘post apocalyptic warzone’ straight-to-video jobs.

44. Amores Perros (2000, Mex.), d. Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu

21 Grams may have grabbed the Oscar headlines, but Alejandro González Iñárritu perfected his techniques in overlapping storylines, stunning cinematography and the creative use of car crashes in this Mexican smash about three separate lives linked together by one common event. Remarkable for its stellar performances from a cast previously unknown outside their home country, for taking the fractured narrative to a whole new level, and for tackling subjects that studios avoid like the plague – dog fighting, anyone? – this burst like a firework on the indie world, and acted as a wake-up call to the US indie scene. You’re not the only ones setting the pace now, guys.

43. Shadows (1959), d. John Cassavetes

Inventing American indie cinema before QT was even born, writer-director John Cassavetes’ debut feature is a rough hewn landmark. Taking a subject matter that ’50s Hollywood wouldn’t touch with a barge-pole – the tensions within a black family arising when a young woman (Leila Goldoni) starts dating white men – Cassavetes ignores all the tricks of the mainstream to jazz up his simple story, instead opting for an almost home movie approach where you are allowed to get under the skin of the central character. It may seem somewhat dated now but as both a document of 60s Bohemian New York and the birth of American indie, this is essential.

42. Swingers (1996), d. Doug Liman

A true indie, this one, given that large sections of this film – in the casino, and on the highway – were shot without the proper permits, while director and stars pretended that the camera was turned off as the cops stood by. But the results of this largely plotless story of friends rallying round their suddenly single pal are undeniable. One of the very best buddy comedies out there, embraced by men the world over as somehow descriptive of their twenties, it’s a perfect example of what happens when that strange alchemy between cast, crew, script and tone all work perfectly.

41. Dead Man’s Shoes (2004, UK), d. Shane Meadows

Most films on this list are here because of the man behind the camera. In this case, and with no disrespect to Shane Meadows’ assured direction, it’s the stunning turn by its star and co-writer, Paddy Considine that’s won it a place. He’s the central character, an ex-soldier who returns to his hometown and brings down a world of pain on the men who bullied his younger brother. A showcase for a deserving actor, and a perfect example of the indie sector’s ability to tackle storylines that studios would shy away from, this is one of the finest British films in years.

40. The Descent (2005, UK), d. Neil Marshall

Howling onto the scene with surprise werewolf hit, Dog Soldiers, Neil Marshall surpassed himself with this claustrophobic follow-up that sees six female potholers trapped in the dark, far underground. Set in the US (where these things more routinely seem to happen) but shot at Pinewood and on location in Scotland, The Descent is by far and away the best Brit horror in years. It’s achievement is unrelenting terror – hell, the film wrings out a succession of solid scares before the film’s primary menace is even introduced! Ultimately a simple concept, this is skillfully executed, with a well-balanced character dynamic underpinning Marshall’s expert grasp of horror filmmaking.

39. The Passion Of The Christ (2004, It./US), d. Mel Gibson

It almost defies belief that an R-rated, independent film, shot entirely in two dead languages went on to make $370 million at the box office. Even more so considering that distributors, mindful of the inevitable controversy, originally wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot Roman spear. But Mel Gibson’s vision did pay off and despite the bluster of indignant religious leaders and the righteous smiting of the Lord (two crew members, including star Jim Caviezel, were struck by lightning during the shoot) the film succeeded: spreading the gospel and raking in an ungodly amount of cash for good measure.

38. Grosse Point Blank (1997), d. George Armitage

John Cusack’s turn as repentant hit man Martin Blank marks the single greatest ’80s throwback, killer-for-hire rom-com ever made. You know the story: boy meets girl, boy stands up girl on prom night, girl’s heart is broken, boy becomes professional killer. It’s an age-old tale and, thanks to Cusack’s charming killer and a fresh-faced appearance from Minnie Driver, manages to be both charmingly romantic (he literally kills for her) and darkly comic. This remains the only film from screenwriter Tom Jankiewicz and a delightfully different romcom that stands head and shoulders above its peers – and boasts a more impressive bodycount to boot.

37. Being John Malkovich (1999), d. Spike Jonze

This film makes the list for one simple reason: it proved, once and for all, that a film doesn’t have to make any sense to be great. Impossible to sum up in any thirty-second studio pitch – low ceilings, puppets, and a sinister conspiracy focusing on John Malkovich’s brain and the New Jersey turnpike are all involved. But what’s great is that Charlie Kaufman’s insane script, Spike Jonze’s delirious direction and a cast of A-listers playing wackily against type somehow add up to one of the cleverest, silliest and utterly weirdest films you’ll ever see.

36. Buffalo ’66 (1998), d. Vincent Gallo

Get it straight – Vincent Gallo doesn’t give a f–k what you think about his movie. It’s brilliant, and if you can’t see that then it’s your own tough luck. He’s so fiercely independent he uses Yes on the soundtrack. And you know what? He’s absolutely right. This film is a mini masterpiece. Using only a small but highly talented crew and cast, he bombards us with belligerent, unlikeable characters for 100-odd minutes, and manages to make the most saccharine of endings – about the power of love, of all things – appetising. A beautifully balanced debut from a precocious talent – surely what indie is all about?

35. THX-1138 (1971), d. George Lucas

Before there was ![]() Star Wars, George Lucas made this dystopian vision of a future in a galaxy quite close by. Robert Duvall plays the eponymous THX-1138, a worker in a society where sex is outlawed and drugs used to control the populace, who rebels and begins the search for a better life. What’s remarkable in this film are the visuals – the sterile, almost colourless world and menacing robot police provide a stark backdrop for the increasingly passionate feelings of the central characters. Lucas’ visions may have become bigger and more colourful as he developed his career, but nothing since has mixed intellectual debate and action so effectively.

Star Wars, George Lucas made this dystopian vision of a future in a galaxy quite close by. Robert Duvall plays the eponymous THX-1138, a worker in a society where sex is outlawed and drugs used to control the populace, who rebels and begins the search for a better life. What’s remarkable in this film are the visuals – the sterile, almost colourless world and menacing robot police provide a stark backdrop for the increasingly passionate feelings of the central characters. Lucas’ visions may have become bigger and more colourful as he developed his career, but nothing since has mixed intellectual debate and action so effectively.

34. The Blair Witch Project (1999), d. Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sanchez

The scariest movie ever made? Of course not but you’d never have known it through the hype that surrounded Blair Witch upon release. Not bad for a film shot for $35,000 on a camera bought at Wal-Mart (and subsequently returned for a refund). The film was almost entirely improvised by the three leads (who were often just as terrified as the audience) and initially passed off as a documentary, a ruse given credence by an entirely fictitious web-based backstory. It’s far from the most frightening cinema experience imaginable but an ingenious piece of creative filmmaking it certainly is.

33. Shallow Grave (1994, UK), d. Danny Boyle

A wave of hype followed this thriller, almost swamping it under proclamations that the British were coming, that Scotland was sexy, that Ewan McGregor might do well for himself. Well, that’s all true – but there’s more to Shallow Grave than a (temporary) reinvigoration of British cinema. Danny Boyle’s immensely stylish tale of dead bodies, a suitcase full of money and rampant paranoia is an inspired blend of pitch-black comedy and bloody violence, held together by career-making performances and scathing wit. Three central characters this flawed are a rare sight in American cinema – even in the independent sector – which, along with the sheer panache of this film, make it a must-see.

32. Two Lane Blacktop (1971), d. Monte Hellman

As much a testament to Godfather of American indie cinema Monte Hellman (he was the rain check director for at least two films on this list) as the film itself, this is his best effort behind the megaphone, and the best of the post-![]() Easy Rider road movies of the ’70s. On the surface it ticks a lot of cliché boxes – European influence (Antonioni), absence of dialogue, arcless characters and an unresolved plot, but rather than coming across as pretentious, it’s precisely this ambiguity – along with the avoidance of simply being a love poem to the open road – that continues to hold audiences.

Easy Rider road movies of the ’70s. On the surface it ticks a lot of cliché boxes – European influence (Antonioni), absence of dialogue, arcless characters and an unresolved plot, but rather than coming across as pretentious, it’s precisely this ambiguity – along with the avoidance of simply being a love poem to the open road – that continues to hold audiences.

31. Pink Flamingos (1972), d. John Waters

Let’s get the dog turd out of the way first. Yes, Divine does wolf down a real live, freshly laid parcel of pooch poo in John Waters’ trashy cult classic, but that’s not reason alone for its place on this list. And it’s not just it’s rather shoddy production values either (independent doesn’t mean badly made). Instead, Pink Flamingos is on this list because of the sheer chutzpah of Waters’ story – two families compete with each to see who can be the most disgusting – and willingness to push back the barriers of tat, taste and what audiences were willing to tolerate waaaaay back in 1972. Without Waters, we might never have had the literal flood of jizz/piss/poo jokes that assailed us all in recent years. Believe it or not, but that’s something to thank him for.

30. Sweet Sweetback Baadassss’ Song (1971), d. Melvin Van Peebles

Made for $50,000 and grossing $10 million, Sweetback was financed, produced, written, directed, scored and starred by Melvin Van Peebles and one of the very few Black movies of the ’70s to emerge from a completely black artistic sensibility. Obscene, frenzied, painful, the movie sees the titular hero go on the run after stomping a couple of cops unconscious, throwing up a series of violent set-pieces that comment on both Black stereotypes and blaxploitation staples. Showing a whole generation of black filmmakers the way forward, the guerrilla filmmaking and canny marketing campaign also provide pointers for every no-budget filmmaker following in its wake.

29. Bad Lieutenant (1992), d. Abel Ferrara

As uncompromising and maverick-minded as its director, Bad Lieutenant is certainly the most notorious, searingly emotional and profound of Abel Ferrara’s back catalogue of scuzz and sleaze. Starring indie darling Harvey Keitel – in a mesmerising and extraordinarily brave performance – as a seriously corrupt, guilt-ridden, devoutly Catholic cop, this is a breathtaking modern-day parable of sin and redemption that is so hardcore, so unflinching in its portrayal of a man’s descent into Hell and his scrabbling attempts to get into Heaven that it simply had to be an independent movie. And we haven’t even mentioned the scene where Keitel quite literally pulls over two girls on the freeway…

28. In The Company Of Men (1997), d. Neil LaBute

Neil LaBute had been a powerful voice in the American theatre for a few years until he turned his hand to cinema, and knocked one out of the park first time out with this bitter, acid-edged , unwavering look at the evil that men do. In this case, the mendacious misanthropy comes from two guys (Aaron Eckhart and Matt Malloy), both recently dumped, who make a bet to toy with the affections of a deaf woman (Stacy Edwards). It – and LaBute – have been accused of misogyny, but the movie – as impassive as it is – leaves us in no doubt that Malloy and Eckhart are the slime of the universe.

27. Dark Star (1974), d. John Carpenter

There are those who will argue that Halloween is the better John Carpenter film, more deserving of recognition here. They’re right and they’re wrong. Halloween is indeed the better film – it was a terrific (in both senses), genuinely scary template for horror for the next decade, while Dark Star is a wildly uneven, low-budget-to the-point-of-impeding-your-enjoyment sci-fi. But the very fact that Dark Star found screens at all, its more creative story content (life onboard the ship being unsatisfactory, the philosophising bomb as a brilliant extension of ![]() 2001‘s self-aware HAL), and the issue that without it Carpenter’s career wouldn’t exist, gets this over the line.

2001‘s self-aware HAL), and the issue that without it Carpenter’s career wouldn’t exist, gets this over the line.

26. Lost in Translation (2003), d. Sofia Coppola

Intelligence and emotional honesty are all too rarely elements that make-up a romantic comedy. Sofia Coppola’s meditation on romantic and cultural alienation, however, strips out the clichés, tired chat-up lines and drunken sex, leaving us with a simple, touching collision of two lost souls. This was a plum role for Scarlett Johanssen and a long-awaited return to form for Bill Murray, coaxing forth what is arguably the best performance of his entire career. While Coppola made her bones as an indie director with her adaptation of The Virgin Suicides, this original story, with its frank but tender realism and wry humour, remains her crowning achievement.

25. Drugstore Cowboy (1989), d. Gus Van Sant

Wanna check the indie credentials of Drugstore Cowboy? OK, never mind that Gus Van Sant – perhaps the most indie-centric, experimental film-maker working just outside the American mainstream today – directed it. Never mind that it’s a non-judgmental look at drug culture and the mindset of a group of people (led by a never-better Matt Dillon and Kelly Lynch) who break into drugstores in order to get their prescription pill high. Never mind that it’s a hazily lensed, at times bleak, at times funny and touching, near-masterpiece, always unflinching but never unfeeling. You want to know why Drugstore Cowboy is an indie film par excellence? William S. Burroughs in it. Like, wow man…

24. Happiness (1998), d. Todd Solondz

A more ironic title you will be hard put to find, as Todd Solondz takes us on a hellish trek through the lives of a string of interconnected misfits. The only thing these people – a phone sex pest and a pedophile among them – have in common is misery. Not exactly the sort of film you go to Disney to get funding for, but that’s never been Todd’s way. Welcome To The Doll’s House is equally eligible in terms of independence, but this is firstly a more accomplished film, plus we’re awarding kudos points for keepin’ it real after the success of his previous feature.

23. The Evil Dead (1981), d. Sam Raimi

The making of the Evil Dead very nearly lives up to the movie’s tagline, ‘the ultimate experience in grueling terror’. In 1979, three Detroit wannabe film-makers – producer Rob Tapert, actor Bruce Campbell and director Sam Raimi decamped to a disused Tennessee cabin to shoot a horror movie about five kids battling demons. They had precious little money, borrowed equipment, no real clue of what they were doing and – by the end – precious little sanity. But necessity is the mother of invention, and The Evil Dead pulses with it. Virtually every horror film-maker of the last 20 years has cribbed from Raimi’s box of camera tricks.

22. Nosferatu, A Symphony Of Terror (1922, Ger.) (aka Nosferatu – eine Symphonie des Grauens), d. F.W. Murnau

Not so much the Granddaddy of indie films, as the mad Great uncle, when F.W. Murnau decided he wanted to adapt Bram Stoker’s Dracula, he didn’t let legal threats stop him – he just changed the names and made a few tweaks. Murnau’s ingenuity (and a court order) gets him in here, but Nosferatu is also one of the best silent films ever made, and one of the creepiest, sound or no. It contributed to making German Expressionism an entire chapter in the cinema history books, and is among the most homaged, pastiched, and parodied films ever made – so indie they had to make an indie film about it.

21. Roger And Me (1989), d. Michael Moore

Before the Oscar-winning Bowling for Columbine and the headline grabbing Fahrenheit 9/11, Michael Moore made a documentary about the closure of the automobile plant in his hometown of Flint, Michigan and the economic devastation that followed it, and it made his reputation. All Moore’s polemic skills are apparent here – there’s the same sly cross-cutting, the persistent hounding of people determined not to talk to him, and interviews with the sort of ‘ordinary’ everyday loons that only exist in small American towns. Arguably better than its successors – Moore punctures pomposity in others without appearing pompous himself – this is rabble-rousing stuff.

20. Slacker (1991), d. Richard Linklater

A prototype for Kevin Smith’s Clerks, the film that launched Richard Linklater’s career is a simple look at a group of twenty-somethings up to not much, really, one summer day in Austin. Free-thinkers all – some would call them weirdos – Linklater’s characters already display the spontaneous, free-flowing dialogue that is his trademark, and the sort of innovative structure (the characters meet, and the camera switches from one to the next) that marks his best work. One of the most influential films on the indie scene, this elevated mood over plot and dialogue over action and showed that a few good characters can make a classic.

19. Lone Star (1996), d. John Sayles

John Sayles has never in his 25 years as a director, helmed within the studio system, making him a rarity: an indie filmmaker that hasn’t a) become part of the system, or b) vanished up his own arse. Lone Star is where Sayles’ technical skills caught up with his storytelling abilities. His familiar theme of contemporary America under the burden of its own glossed-over history is folded into a murder mystery ensemble piece, spanning two Texan generations, and utilising some of the best flashbacks ever seen. It’s brilliant, it’s intelligent, and it’s refreshingly beyond Hollywood.

18. Withnail And I (1987, UK), d. Bruce Robinson

Another entry from Brit mini-production house Handmade, this is one of those masterpieces that almost didn’t happen. Producer Denis O’Brien hated the first rushes, threatening to fire writer / director Bruce Robinson – who had already quit once already before lunch on the first day. The film is possibly one of the finest on-the-page screenplays ever written, brought to life with an understated style that the mainstream simply wouldn’t dream of attempting. Sadly much of its popularity has been within the student community, who still believe that endlessly quoting the lines (often incorrectly) will make them as funny as the title characters, but don’t let that sour the genius.

17. City of God (2002, Braz.), d. Kátia Lund, Fernando Meirelles

There can be no greater commitment to filmmaking than putting your life on the line to tell a story. Such are the lengths Fernando Meirelles, Katia Lund and their crew went to while filming City of God in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Shooting (and trying to avoid being shot) among the gangs and street violence of and recruiting a cast from the slum kids themselves, they retell a true story of crime, corruption, degradation and a complete disregard for human life in ’60s Rio’s most notoriously violent slum. Heavily improvised and impressively performed, City of God is a powerful, beautiful film that’s as emotionally devastating as it is technically stunning.

16. She’s Gotta Have It (1986), d. Spike Lee

Non-union actors, no retakes, a director who demanded that his actors keep their drinks cans for the recycling money – budgets don’t get much lower than this. Debate still rages about whether the plot – about a woman with three different boyfriends to provide different emotional and sexual needs – is a marvel of feminist filmmaking or misogyny of the worst sort, but either way the film’s humour and lively characters brought Spike Lee to the attention of audiences and paved the way for his particular outlook on life. And since he was, until the arrival of John Singleton at least, the only major African-American director in Hollywood, that’s an important perspective to have.

15. Blood Simple (1984), d. Joel Coen

The Coen Brothers launched themselves upon an unsuspecting world with this noir throwback in 1984, and they haven’t looked back. But all their subsequent success – and many of their trademark flourishes – can be dated back to this Texas-set tale of private eyes, murder most foul and more double (triple, and quadruple) crosses than you can count. The style is present and correct in the almost black-and-white locations and bright red blood, but it’s the tone that stands out. Like Fargo without the warmth of Marge Gunderson, or Miller’s Crossing without the qualms of conscience, Blood Simple is the darkest, and arguably up there with the best, of the Coens’ films.

14. Stranger Than Paradise (1984, W. Ger/US), d. Jim Jarmusch

Jim Jarmusch is another in the small canon of American directors who have spent their entire career outside of the mainstream – hell, even when he’s got Johnny Depp in his movie the box office seems relatively unperturbed. But it’s this early work – just his second feature – that stands among the best. Possibly the biggest reason for Stranger Than Paradise‘s inclusion here is, despite all outward appearances, Jarmusch’s craftily disguising that he knows exactly what he’s on about. It wasn’t for another film or two that his themes of the universality of humankind, regardless of race, creed or colour, became apparent. Consider also his legacy on the likes of Wayne Wang and Greg Araki.

13. Memento (2000), d. Christopher Nolan

Christopher Nolan’s modestly budgeted sleeper hit managed to claw it’s way over the indie fence and into mainstream recognition on pure ingenuity. Before Memento, the ‘character with amnesia’ subgenre was, generally, a rather tired one (and has become so again since), but using the simplest of devices – telling the story’s episodic structure in reverse order – the filmmakers (Nolan’s brother Jonathan wrote the basis of the screenplay) forged a tale that was arse-clenchingly compelling, and ironically, unforgettable. And let’s not forget it was the first major breakthrough in screenwriting structure since Pulp Fiction and its many clones, which in itself deserves an award.

12. Eraserhead (1977), d. David Lynch

Another piecemeal movie – shot over five years on a virtually non-existent budget, prompting lead Jack Nance to keep that same distinctive pre-Marge Simpson haircut for the duration of the shoot – Eraserhead is one of the strangest, most perplexing movies you’ll ever see. It’s jam-packed with deeply unsettling imagery, a grating, scraping, percussive soundtrack and an almost omnipresent sense of dread and doom. Despite all that, it’s one of Lynch’s most complete, a true surrealist masterpiece for everybody, barring the guy who made it – in Lynch’s world, this is probably the equivalent of Bad Boys 2.

11. Bad Taste (1987, NZ), d. Peter Jackson

Compared to the long hard slog that was making Bad Taste, the Rings trilogy was a walk in the park. Famously funded almost entirely by himself and shot on weekends over a period of FOUR YEARS, Jackson not only wrote, directed, and appeared in a couple of roles, but supervised the special effects, constructed makeshift ‘steadicam’ equipment and probably made the tea, too. The result is as ramshackle as you’d imagine, but is also an endlessly inventive, vibrant alien invasion movie with extraordinary levels of gore, black comedy and an early peek of the scampish, OTT sense of humour that is evident in even the most serious and worthy of PJ’s canon. At times you can almost hear him giggle himself silly, behind the camera.

10. Mean Streets (1973), d. Martin Scorsese

Father Martin Scorsese. Stated simply like that, those three words just don’t scan correctly, but if Martin Scorsese – the greatest living director never to win an Oscar – had gone with his first love, the priesthood, instead of his second, making movies, we’d never had GoodFellas, or ![]() Raging Bull, or

Raging Bull, or ![]() Taxi Driver, or Kundun. OK, maybe forget the last one, and replace it with Mean Streets which, to this day, remains probably Scorsese’s most personal and powerful work. A strange mixture of seedy violence, frank nudity and the sort of language you’d expect to hear from gangsters in New York’s Little Italy, the film is nonetheless drenched in a veil of Catholic guilt (lead Harvey Keitel, as Charlie, a small-time hood who knows that he should get the hell out of the game, constantly chastises and tests himself) and seems to act as a permanent celluloid confessional for Scorsese’s baser instincts. For this alone, this gritty little drama would be worth noting, but it’s also shot through with hints of Scorsese’s virtuosity (the wonderful pop-infused soundtrack, and the scene where a drunk Keitel teeters through a bar in one disorienting shot), and tantalising glimpses of his future preoccupations: gangsters, the mores of masculinity and a rich and varied partnership with one Mr. R. De Niro, so magnetic here as wildcard wiseguy, Johnny Boy.

Taxi Driver, or Kundun. OK, maybe forget the last one, and replace it with Mean Streets which, to this day, remains probably Scorsese’s most personal and powerful work. A strange mixture of seedy violence, frank nudity and the sort of language you’d expect to hear from gangsters in New York’s Little Italy, the film is nonetheless drenched in a veil of Catholic guilt (lead Harvey Keitel, as Charlie, a small-time hood who knows that he should get the hell out of the game, constantly chastises and tests himself) and seems to act as a permanent celluloid confessional for Scorsese’s baser instincts. For this alone, this gritty little drama would be worth noting, but it’s also shot through with hints of Scorsese’s virtuosity (the wonderful pop-infused soundtrack, and the scene where a drunk Keitel teeters through a bar in one disorienting shot), and tantalising glimpses of his future preoccupations: gangsters, the mores of masculinity and a rich and varied partnership with one Mr. R. De Niro, so magnetic here as wildcard wiseguy, Johnny Boy.

9. Sideways (2004), d. Alexander Payne

Alexander Payne had already impressed audiences with a high-school satire (Election) and a witty tale of an old man’s voyage into retirement (About Schmidt), but it was this one – gently and intelligently picking apart the foibles of middle-age life – that blew the critics away and confirmed his status as an arthouse auteur to be reckoned with. The deceptively simple tale of two mismatched friends who take a weekend in the wine country is simply one of the best character studies you’re ever going to see. It’s got it all: laughs (try to keep a straight face as Paul Giamatti flees the fat naked man), sadness (the Pinot Noir speech is heartbreaking) and a wonderfully uplifting, surprising ending. And consider this – if this had been a studio film, Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church would have been bit-part players, instead of the leads (who might well have been George Clooney and Tom Hanks). For that fact alone, Sideways is worthy of its place in the top ten.

8. The Usual Suspects (1995), d. Bryan Singer

It’s a film that gained fame and acclaim primarily on the strength of that ending, but The Usual Suspects is far more than just a crime yarn with a clever twist. Inspired only by the concept for its poster (five guys in a line-up), Christopher McQuarrie’s mind-bending heist thriller is nothing less than an ensemble tour de force and, lest we forget, the starting pistol for both Bryan Singer and Kevin Spacey’s careers in the big time. The basic plot – a collection of career criminals are rounded up for a heist, decide to join forces for a job but soon find themselves on the wrong side of a legendary underworld figure – hardly does justice to the bigger picture, which is gradually assembled from a series of flashbacks. Sleight of hand and misdirection are the tools used here, the film leading viewers by the nose, playing with our perceptions before quite violently pulling the rug from under us. Complemented by a cast on top form – Stephen Baldwin and Benicio Del Toro provide the laughs with Gabriel Byrne adding a pleasingly sinister turn – The Usual Suspects is a masterwork of modern filmmaking, as simple in inception as it is elegant in execution.

7. sex, lies, and videotape (1989), d. Steven Soderbergh

Steven Soderbergh wrote this in eight days, and filmed it in five weeks on a budget of $1.2 million. The words “jammy git” should leap to mind, but subsequent films have proved him to be consistent in the freakishly talented stakes. This, his debut feature, won him the Palm D’Or and an Oscar nomination, courtesy of the brilliant screenplay and some unexpectedly deep performances from all four lead actors – nearly-was teen idol Spader, first time lead MacDowell, and then unknowns Laura San Giacomo & Peter Gallagher. Soderbergh understood his subject (voyeurism and secrecy) perfectly. It’s one of those films where ostensibly not much actually happens, but the director’s use of first-person camera within the story rang the voyeuristic bell of a pre-Internet audience. It was the template for a pattern of shaking up financially economic cinematography to be employed by Soderbergh time and again (The Underneath, The Limey, Traffic, et al.) S, L & V generated enough of a buzz to revive the ailing Sundance Festival, and provide Miramax with their first big success (Pete Biskind’s “Down And Dirty Pictures” makes for some terrific further reading on that particular subject). And two years prior to Tarantino’s arrival, it awakened a new generation to the possibilities of low-budget filmmaking.

6. Night of the Living Dead (1968), d. George Romero

Night of the Living Dead is the ultimate yin/yang example of indie film-making. The movie itself is a brilliant, bleak, black-&-white true horror classic, the standard-bearer for a wave of realistic frightflicks that flooded the ’70s and beyond, and of course the movie without which the recent zombie revival would never have happened. At that fledgling stage, George Romero’s technical skills were less than refined, and the shoestring budget – borrowed from local Pittsburgh companies and friends of friends – more than shows itself, but the true horror of a zombie takeover and siege situation is adroitly realized. And with that final, truly gutwrenching shot, Romero begins to expound on a theme that haunts him to this day: the bad guys aren’t them. It’s us! OK, so the film is all well and good, but the financial morass that swamped Romero afterwards is a warning signal to all would-be film-makers – with so many fingers in financial pies, the venerated director has never had control of the rights, which explains why so many different versions of Night are swarming around on DVD, including that dreadful colourised version. But all’s well that ends well, with Land of the Dead hitting cinemas any second now…

5. Monty Python’s Life Of Brian (1979, UK), d. Terry Jones

Most of us know by now the origins of Python’s second proper movie – at a press conference, Eric Idle laughingly suggested that their next project would be “Jesus Christ – Lust For Glory”. What they eventually came up with was much better – an unrivalled satire on religion, and quite possibly the funniest movie ever made. Trouble was, no-one in the film business had the balls to make it. From it’s opening sequence (the first joke is a pratfall) it’s evident that it’s going to be Python of the highest standard, but it’s the cohesion of the story that makes this all work so well. In sending up not Christ, but all of the petty, political, opportunist zealots around him, they had finally found in their subject, an idea ripe for ridicule large enough to accommodate their rapid gag rate and broadness of style. Of course, Brian isn’t the messiah (that’d be the boy up the street), but you try telling them – and the financiers – that. Enter Empire’s favourite Beatle and cornerstone of the British film industry for the next decade, George Harrison (and his money), and the rest is history. The creation of Handmade Films. Uproar. Outrage. Censorship. Genius.

4. Clerks (1994), d. Kevin Smith

All told, the credit card bills and sundry expenses amounted to somewhere in the region of $25,000. That’s a lot of coin to pay back, but if Kevin Smith was ever worried about recouping his borrowed, begged but absolutely not stolen outlay for his first movie, then he didn’t really have time to show it. For Clerks was quickly picked up by Miramax chief Harvey Weinstein, who overlooked its dodgy production values, ropy acting and a story that resists the description ‘threadbare’ because he saw a raw vitality in its balls-out dialogue; a vitality and spirit and, more importantly, laugh out loud sense of humour that ensured that Clerks connected instantly with disenfranchised tweens and shop workers everywhere, and the rest is history for Smith, from Chasing Amy to the continuing adventures of Jay & Silent Bob, to domination of the geek world.

3. The Terminator (1984), d. James Cameron

Its studio-friendly sequels and slick ’80s action sequences may make this appear part of the Hollywood establishment, but look a little more closely. Behind the impressive effects you’ll see an untried director, an obscure leading man and a (relatively) shoestring budget – in fact, all the hallmarks of an indie movie. If you want an example of independent spirit, there’s no finer example than the man behind The Terminator‘s apocalyptic vision. A nobody on the verge of being fired from his job on a silly horror flick about piranhas, James Cameron was fired up by a vivid nightmare he had one night about an unstoppable metal assassin. Hastily scribbling a screenplay and assembling a crew, he threw himself body and soul into the shoot, creating a whole new genre of techno-noir along the way. That The Terminator spawned one of the biggest sequels ever is testament to what a high concept and assured execution can do. Of course, it helps to have a healthy dose of iconic lines and, in Arnold Schwarzenegger, an unstoppable machine from the future – sorry, Austria – poised on the very brink of superstardom.

2. Donnie Darko (2001), d. Richard Kelly

Was Donnie schizophrenic? Is he, in fact, a supernaturally empowered avatar chosen by unknown forces? Did any of the film’s events even happen? Such are the questions that sent people running to the pub to debate just what the hell Kelly had in mind when he wrote this story. That of a teenager who’s warned about the end of the world by a six foot, talking rabbit after a jet engine falls on his house. Part supernatural chiller, part ’80s teen drama and part philosophical musing on wormhole theory and the transience of human existence. Donnie Darko is not a film that lends itself to easy categorization and, unwilling to compromise his convoluted vision for studio palates, 27-year-old writer/director Richard Kelly almost had to launch his debut on cable television. Luckily, though, this exquisite slice of sci-fi surrealism was rescued from the precipice of DTV and went on to become a cult hit while simultaneously placing Jake Gyllenhaal on the road to stardom. A bizarre concoction it undoubtedly is but Donnie Darko raised the bar for independent thinking and reinvented the teen genre for the new Millennium. Utter genius.

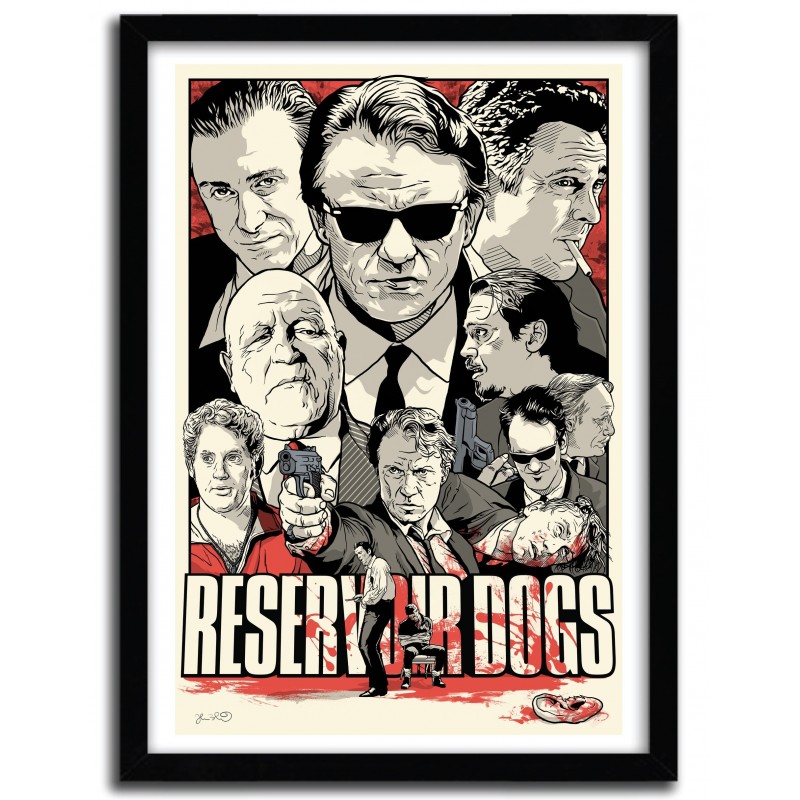

1. Reservoir Dogs (1992), d. Quentin Tarantino

Some will bleat that this is an easy, obvious choice, while others will say… well, pretty much the same, but nominate differently. Our criteria for deciding the films were: firstly, the circumstances and spirit in which they were made, second, the quality of the result and, finally, its mark on the movie world. This is how Reservoir Dogs gained consensus as the winner. Consider firstly the film’s creation: script written in two weeks while the author was in a dead-end day job, it barely changed from first draft to shooting script, and attracted attention by word of mouth. It garnered rave reviews, but Dogs‘ box office performance wasn’t great – again, it had to wait for word of mouth. Most importantly, the magnitude of effect this one film has had on indie culture in the last 13 years is, to say the least, overwhelming. The fact is that more than one generation has had their eyes opened to the long-snubbed world of movie-making’s outsiders, be it American mavericks, foreign actioners, or just plain old B-pictures. If it wasn’t for Dogs, Hong Kong action cinema would still be a lot more marginal than it is today, and nobody would likely have got around to transferring blaxploitation titles onto DVD yet. You only have to look through the homages and ripoffs that have abounded – how many more films have suited gunmen, feature heists gone wrong, have people talking about pop culture, or ‘boast’ a fractured narrative? Love or hate it, Reservoir Dogs is the greatest independent movie ever made.