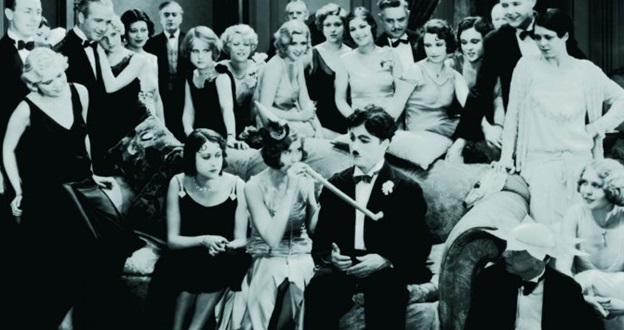

Charlie Chaplin in ‘City Lights’/Image © 1931 Warner Bros.

The Jazz Age, much like the 1960s, was a period of rebellion, a time when social mores were broken down, and everything changed. Women cut and bobbed their hair. They wore lipstick and shortened their skirts. Men carried flasks and drove around in cars, which also served as excellent places for sexual experimentation. It was also a time of deep personal and societal struggle.

To my mind two of the most important films reflecting the Jazz Age were made during that era: “The Jazz Singer” with Al Jolson, and Charlie Chaplin’s masterpiece, “City Lights.” In “The Jazz Singer,” Al Jolson famously plays a young Jewish singer, groomed to be a cantor but who wants to be a jazz singer. The film, which is also famous for being the first talking film, shows the internal struggle of the Al Jolson character. If you can overlook the fact that Jolson performs in black face, it’s a heart-wrenching tale, beautifully performed, and it has earned its place as a classic.

Another classic that I think truly reflects the era is Charlie Chaplin’s iconic “City Lights.” One of the amazing things about “City Lights” is that it is a silent film that was made in the era of talking films. But Chaplin didn’t want this film to be a talkie. He felt it diluted his art. It took him two years to make and many consider it his masterpiece. In the film, The Tramp, played of course by Chaplin, falls in love with a blind girl. At the same time, he winds up in the company of a wealthy scion who, when he’s drunk, befriends the Tramp. When he sobers up, he kicks the Tramp back onto the street. More than anything, “City Lights” is a film about class in an urban environment, and of course in the backdrop are drunken parties, flapper dresses, and the implication of wild sex, all churning around the Tramp and his innocent love for the blind girl whom he fears, once she can see, will reject him because of his poverty.

When we think of the Jazz Age, we often envision one long, wild party and in some ways that image is true. Or at least it has been reinforced by films that reflect it in that way. Elia Kazan’s wonderful 1961 “Splendor in the Grass” captures that time when social and sexual morals were changing. Warren Beatty, in his first feature, plays a young, star school athlete, Bud Stamper, and the beautiful ingénue Natalie Wood plays his loving but virtuous girlfriend, Deanie Loomis. Set in 1928, their burgeoning sexuality is at odds with the constraints of the society in which they live. It’s fascinating that the story is set in Kansas. It’s Oz. It’s the heartland. It’s the true heart of America. Bud and Deanie try to resist their sexual yearnings and love for one another, and this leads to heartbreak. All of this plays out against scenes of wild parties (especially on New Year’s Eve), hot sex, and plenty of alcohol consumption – a good portrait of the era.

Just as “The Jazz Singer” and “City Lights” are about family and poverty, inner conflict and class struggle, “The Great Gatsby” is about longing for what perhaps always was an illusion. Just as the book came to represent the era, so has the film. I’m not referring to the deliciously terrible Leonardo DiCaprio version, but rather the more sedate and nuanced Robert Redford. Redford perfectly captures that time of dreaming and romance, when you were either looking at the world through a champagne bubble – or a Saturday night special.

“The Cat’s Meow,” made by Peter Bogdanovich in 2001, again captures that world of longing and desire, all set to the tune of “Charleston.” It is the story of the mysterious death (and most likely murder and a cover-up) of the film producer Thomas Ince on William Randolph Hearst’s yacht. Hearst, played brilliantly by Edward Hermann, who recently died of cancer, shows the power that wealth and the press have and the undeniable truth that money cannot buy love. Perhaps the most compelling performance is Eddie Izzard’s Charlie Chaplin. He portrays Chaplin as a sex-crazed, manipulative man who thought nothing of getting young girls pregnant or poaching on Hearst’s longtime mistress, the actor Marion Davies. This film also has a terrific soundtrack of the era.

And a more recent, just-for-fun film to look at for a sense of the Jazz Age is Woody Allen’s deliriously dreamy “Midnight in Paris,” in which each night at midnight in Paris an unhappily married composer, Owen Wilson, finds himself very happily transported back to Paris in the 1920s.

It’s a time we’d all like to go back to, isn’t it? And these films are one way to do so.

By MARY MORRIS

Mary Morris teaches writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Her novels include Revenge, Acts of God, House Arrest, The Night Sky, and The Waiting Room. She has also authored two collections of short stories and four memoirs about her extensive travels. Her latest novel, The Jazz Palace, a coming-of-age novel set in Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, is available now. Find out more at marymorris.n