PARIS — The French comic book artist Yvan Alagbé consistently gets the same question about his work: “Why do you always draw black people?” His interrogative reply is twofold: “Have you ever once asked a white person why he only draws white people?” and “Is it not possible for me to draw a black person who is representative of humanity in general?”

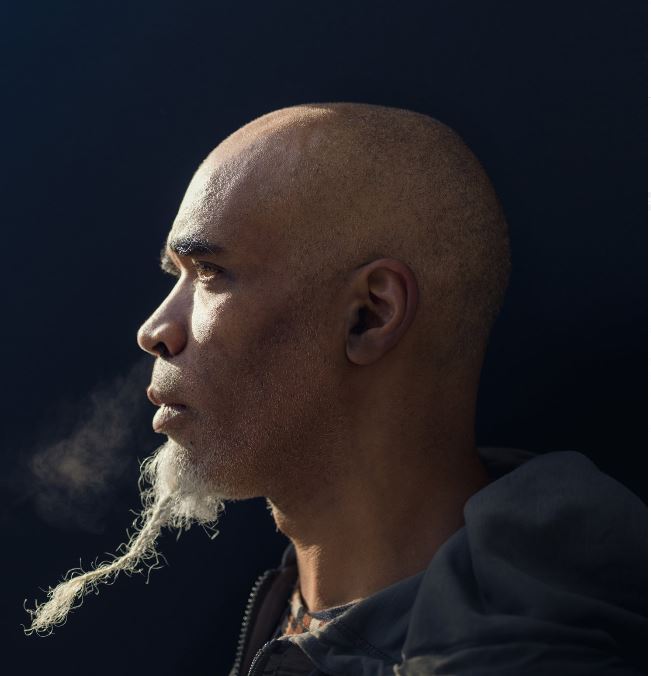

With his twisted goatee and shaved head, Mr. Alagbé cut a shamanistic figure as he calmly surveyed the teeming hordes at the annual Children’s Books Fair in Montreuil, a suburb just east of Paris. As a co-founder of the comic book publisher Fremok he has been attending the event, where we met at the end of November, every year for the last 17 years.

Though not a children’s book, Mr. Alagbé’s “Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures” is popular among the world of French comics. It was published in 2012 in France, and has now been translated into English and is being released by New York Review Comics on April 3. The 47-year-old author began “Yellow Negroes” more than 20 years ago and has been adding narrative layers to it on and off ever since. It has been compared to Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” by the art historian and comic book critic Matthias Wivel.

Though not a children’s book, Mr. Alagbé’s “Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures” is popular among the world of French comics. It was published in 2012 in France, and has now been translated into English and is being released by New York Review Comics on April 3. The 47-year-old author began “Yellow Negroes” more than 20 years ago and has been adding narrative layers to it on and off ever since. It has been compared to Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” by the art historian and comic book critic Matthias Wivel.

Similarities include its long gestation, exclusively black-and-white palette and Mr. Alagbé’s willingness to tackle social and historical issues in comic book form. “A lot of comic book authors are still stuck in the past and are using the same conventional forms as Hergé did in the 1930s,” Mr. Alagbé said in a recent interview. “That’s not a problem per se but it shouldn’t be at the expense of comic book authors who want to do something that is not conventional.”

In “Yellow Negroes” Mr. Alagbé did not use black ink naturalistically but as something more expressionistic. An unclothed black man lying asleep on a bed, for instance, might be left with just an outline as opposed to being shaded so as to emphasize his nakedness. “That’s something that even now is quite rare in comic books,” Mr. Alagbé said. “In American comic books blacks have tended to be uniformly black.”

Mr. Alagbé’s goal with “Yellow Negroes” was “to tell stories about people who have been marginalized by society.” These range from the travails of undocumented African migrants eking out a living in Paris to the frowned upon relationship of a mixed race couple. The title of Mr. Alagbé’s book came instinctively to him, but with hindsight he said it speaks of “racial labeling which is actually an absurdity.”

Mr. Alagbé’s own upbringing taught him as much. The son of a white French mother and a black Beninese father, Mr. Alagbé was born in France but spent his childhood from 6 to 9-years-old living in Benin. “A yellow negro is someone who has my skin color,” he said. “When I lived in Benin in a neighborhood where there was a mix of ethnicities I was considered white. When I tell this story in France people are amused because for them I’m black.”

Mr. Alagbé’s surrogate in the book is Sam, a light-skinned struggling illustrator living in Paris, who narrates his encounters with an assortment of damaged souls. One of those is Mario, a former police officer who hails from Algeria. The character was inspired by a man Mr. Alagbé met when he was living with his father in Paris during the 1990s. In the book Mario pathetically tries to buy the affections of a Beninese brother and sister by offering to provide them with working papers.

It gradually emerges that Mario was once part of a brutally repressive auxiliary police force in Paris made up of Algerian Harkis sympathetic to the French occupation of Algeria. He is a haunted, hopeless man. “But instead of helping him people give him a wide berth as if his problems are contagious,” Mr. Alagbé said. Any simple-minded sentimentality about immigrants all being in the same boat is entirely absent from “Yellow Negroes” where everybody is potentially somebody else to exploit.

Mr. Alagbé’s book reminded its English translator Donald Nicholson-Smith of the American underground comics of the 1970s such as “Inner City Romance.” “Not in the style but the subject matter which were all about people living on the edge in the middle of the ghetto,” Mr. Nicholson-Smith said. The English-language version of “Yellow Negroes” is part of New York Review Comics’s drive to unearth foreign gems that have built up a cult following.

The translation feels timely because “Yellow Negroes’” twin themes of undocumented migrant workers and the damaging legacy of European colonialism have not gone away. “Relatively speaking, in France we don’t let any immigrants in anymore,” said Mr. Alagbé, who provided an illustrated coda to the American version of “Yellow Negroes” updating its themes.

“Europe has become a kind of fortress where misfortunates do not have a place. For me that in itself is a kind of hell,” he said.

What has added insult to injury for Mr. Alagbé is that in the meantime France has continued to shape its former African colonies in its own image by erasing the past as it sees fit. In “Yellow Negroes” he reported on a collective of undocumented workers striking in Montreuil who put up a photograph of Thomas Sankara, Burkina Faso’s revolutionary president from 1983 to 1987, in the window of their headquarters

Inserting himself into the narrative, Mr. Alagbé remarked that when he once looked up Sankara’s name in France’s famous Larousse dictionary there was no entry for him. However there was an entry for Blaise Compaoré who led the 1987 coup d’état during which Sankara was assassinated. “I thought that was incredibly violent,” Mr. Alagbé said. “Not only was Sankara assassinated but he was also erased from French history.”

Mr. Alagbé’s other comic books include 2004’s “Who Has Known the Fire” which stages a hypothetical conversation between Sebastian I, who was king of Portugal during the 16th century, and Béhanzin, who became king of Dahomey (now Benin) during the 19th century. His interest in history extends to making light of his own fraught upbringing: He based a husband who abandons his wife in “Yellow Negroes” on his father giving him the name Augustus after the Roman emperor.

Mr. Alagbé cited the films of Pier Paolo Passolini and Rainer Werner Fassbinder as key influences on his work. “Both directors showed the harshness of human relationships where mistrustfulness is ever-present,” he said. Their open-mindedness also touches him in a way that some comic book artists struggle to do. “I’ve chatted with illustrators who have told me that they are so used to drawing white people all the time that when they draw a black person it’s a problem for them,” he said.

Making art for art’s sake has never interested Mr. Alagbé and the sheer quantity of comic books on offer nowadays does not necessarily constitute a golden age for him. “What I’m interested in is work that renders visible what has previously been invisible,” he said. “But you need to look long and hard before that can happen.”