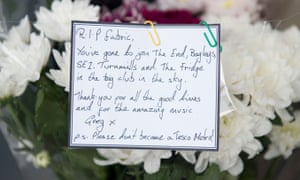

Fabric closure sparks alarm about future of London’s nightlife

Islington council’s decision to revoke club’s licence is condemned across political spectrum

The closure of Fabric, one Britain’s best known nightclubs, has prompted alarm about the future of the clubbing scene and concerns that it is being driven underground as councils attempt to gentrify their areas.

In the early hours of Wednesday morning, Islington council decided to revoke Fabric’s licence after a review prompted by the drug-related deaths of two 18-year-old patrons within nine weeks this summer. In a decision backed by the Metropolitan police, it claimed searches of people entering the club and supervision within was inadequate, ignoring protests by leading dance music figures and a 150,000-strong petition demanding the venue be saved.

Supporters vowed to pursue legal and political avenues to keep it open and there was condemnation from across the political spectrum, from the novelist Irvine Welsh to the rightwing thinktank the Adam Smith Institute, as well as from drug safety campaigners.

More than half of London’s clubs have closed in the last eight years, according to the London mayor, Sadiq Khan, who said this decline had to stop “if London is to retain its status as a 24-hour city with a world-class nightlife”.

Welsh, whose books including Trainspotting and Ecstasy chronicled the drug and clubbing scene in the 1990s, said the closure of Fabric was the “beginning of the end of our cities as cultural centres, and indeed as entertainment centres in the traditional sense”.

He said concerns about drugs were being used as a pretext to close clubs, claiming Fabric was the “least druggy club in London”.

He told the Guardian: “It’s all about property development. In the epoch of neoliberalism and corporate elites, entertainment is being privatised, and will increasingly take place with gated communities, owned and rented out by largely foreign investors.

“The cities need to be kept as sterile and unthreatening as possible for the new overseas owners of them, who can then get trashed behind closed doors or in the mini-club facilities built into their apartment complexes.”

Welsh suggested that future clubbing would take place in shanty towns. “The tent cities and makeshift communities that will grow up on the outskirts of cities, like in the developing world, will be the places to go for a proper party,” he said.

Welsh’s comments were echoed by the editor of Mixmag, Duncan Dick.

“Clubs find themselves in a perfect storm of gentrification and development,” he said. “Although clubs offer massive cultural benefits to the area, are what makes a city, give a city its character, property is king.”

He compared the plight of Fabric to that of the Glasgow superclub the Arches, which closed last year, where he said a luxury hotel was being developed. Dick claimed that more people had died from drugs at a fast food restaurant around the corner from the Arches and yet the club was scapegoated.

While there has been a boom in dance music festivals, Dick said clubs were where “DJs cut their teeth and new genres like dubstep emerge”.

He added: “There’s plenty of people dancing and making music but it will move further out as the developers push them out. Maybe in 20 years the clubbing hotspot will be Luton. You’re not going to stop people wanting to go out and dance but right now it’s looking as if London’s claim to be the centre of nightlife in the world is being eroded.”

The DJ Goldie threatened to melt down his MBE in protest at the closure. Goldie, whose real name is Clifford Joseph Price, told Channel 4 News on Wednesday: “This country was built on being different and being out there musically and from an artistic point of view.

“I’m wondering whether or not the likes of me, the likes of Jazzie B, Norman Jay, Pete Tong for that matter, should just trade our MBEs in, melt them down and put them in a pencil-pusher’s coffee, so it can taste a little bit sweeter for him today, so he feels more successful in killing counter-culture and culture itself.”

Drugs charities warned that closing Fabric would actually increase the risk for clubbers by moving them into unregulated environments.

Danny Kushlick, director of Transform, said: “It’s a disaster. The point is, if there was some risky drug taking going on there then you throw harm reduction services at it. This is a long-established principle since we introduced needle exchanges, free condoms. This decision flies in the face of all our experience of dealing with drug use.”

He blamed the council’s decision on the failure of the licensing process to prioritise public health.

Katy McLeod, director of Chill Welfare, a social enterprise dedicated to keeping clubbers safe, suggested the recent deaths at Fabric were likely to be linked to the emergence of high-strength ecstasy pills rather than any management failings.

“Fabric was probably one of the gold standard clubs in that they had awareness of drug problems,” she said. “People will [instead] go to house parties, underground raves, that have no licensing, drug policies.

“Shortly after the Arches closed, there was a cluster of deaths. There was intelligence to suggest many of them weren’t in nightclub settings; they were in house party settings.”

McLeod warned that making searches more stringent was not necessarily the answer as it merely encouraged “pre-loading” – people taking all their drugs in one go before entering the club.

Sam Bowman, the executive director of the Adam Smith Institute, said the decision to revoke Fabric’s licence was a disgrace.

He said: “The objective should be to reduce harm to drug users and the way to do that is to let them know what they’re using. That means testing drugs that are circulating in clubs and warning drug users if potentially dangerous batches are around – a scheme that has been piloted by some clubs in the past.”

London’s mayor, who unsuccessfully campaigned to keep Fabric open, conceded that steps needed to be taken to ensure that clubbing was safe. Khan said: “The issues faced by Fabric point to a wider problem of how we protect London’s night-time economy, while ensuring it is safe and enjoyable for everyone.”

He confirmed plans to appoint a “night tsar” modelled on Amsterdam’s “night mayor” to do more to promote and protect London’s nightlife, including clubs and venues.

Khan said: “No single organisation or public body can solve these problems alone – we all need to work together to ensure London thrives as a 24-hour city, in a way that is safe and enjoyable for everyone.”

The club’s owners temporarily shut the venue in August to allow an investigation to take place after the death of the second teenager, who collapsed outside the venue. The other died after he fell ill inside the venue in late June. The club said it had operated without incident in the previous two years.

Responding to the council’s decision, the owners said: “Closing Fabric is not the answer to the drug-related problems clubs like ours are working to prevent and sets a troubling precedent for the future of London’s night-time economy.”

An Islington council spokesman said: “The decision of Islington council’s licensing committee on Fabric’s licence was based solely on the evidence, submissions and representations put before the committee.

“To suggest anything else is simply wrong. For the avoidance of doubt, Islington council is not the owner of the building and has no financial interest in the site.”