This is a guest post by The National Museum of Rollerskating Trustee Alan Bacon.

The following article is indebted to the Master of Arts thesis by Romy Poletti titled Residual Culture of Roller Rinks: Media. The Music & Nostalgia of Roller Skating. It was produced in 2009 at McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

This manuscript first became known to me when reading Tom Russo’s book, Chicago Rink Rats: The Roller Capital in Its Heyday. The thesis is listed in the book’s selected biography. To access the full manuscript, go HERE

Poletti referenced the NMRS: “The National Roller Skating Museum Press in Lincoln, Nebraska, produces the most comprehensive work on the history of roller skating.” Poletti also quoted from James Turner, NMRS trustee emeritus’, book, The History of Roller Skating; Sarah Webber’s book, The Allure of the Rink: Roller Skating at the Arena Gardens; and Morris Traub’s Roller Skating Through the Years: The Story of Roller Skates, Rinks, and Skaters. All these books can be purchased from the NMRS.

This article will focus on Poletti’s observations about the importance of music to roller skating, particularly in the Golden Age and Roller Disco eras. The thesis discussed other historic topics that would be interesting to explore in future articles: The role roller skating has played in cinema, the comparison between dance halls and roller rinks, roller skating and nostalgia, and roller skating in the African-American community.

Anyone who has been to a roller skating rink for a public session or a competitive arts meet knows the importance of music to roller skating. The first written account of roller skating is of Joseph Merlin skating while playing the violin. Later on roller skaters were incorporated into a few important ballets. From the beginning of roller skating until today, music has played an integral part in the roller skating experience.

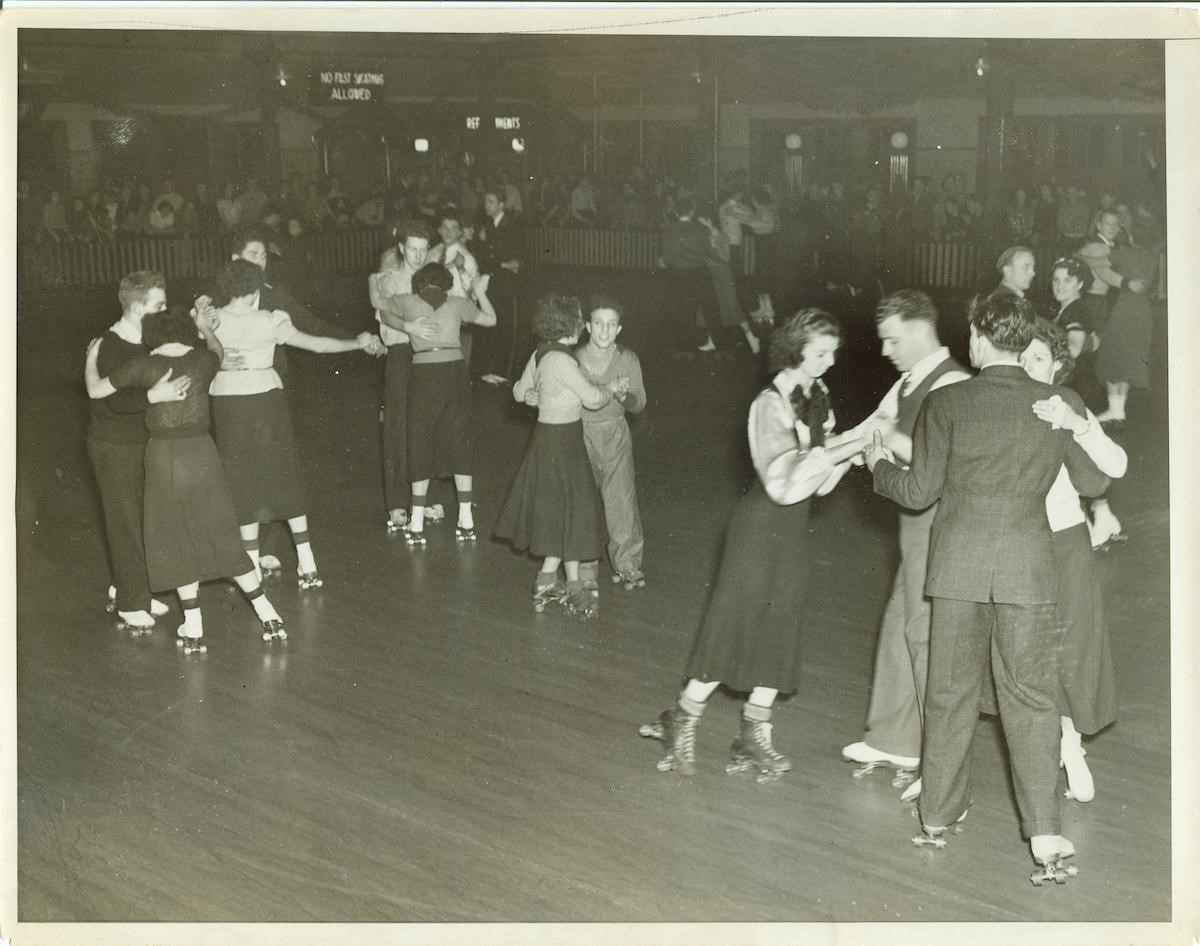

The term the Golden Age of roller skating has been used by Brooks, Russo, Poletti and others to describe the boom in roller skating between 1937-1950 (though dates may differ between authors). Also, the term Roller Disco era is commonly used today to describe the roller skating boom between 1977-1981. (Again, dates may differ slightly.) At first glance, the music of these two eras might seem radically different. However, Poletti emphasized their commonality.

“During the most significant eras in the history of roller-skating culture in the 20th century . . . roller skating was intimately bound up with music. In both of these periods in roller skating history, the rise and decline of skating’s esteem within popular culture were connected to the use of music,” said Poletti. “The popularity of roller skating during those two specific eras is the result of a symbiotic relationship between rink music and movements.”

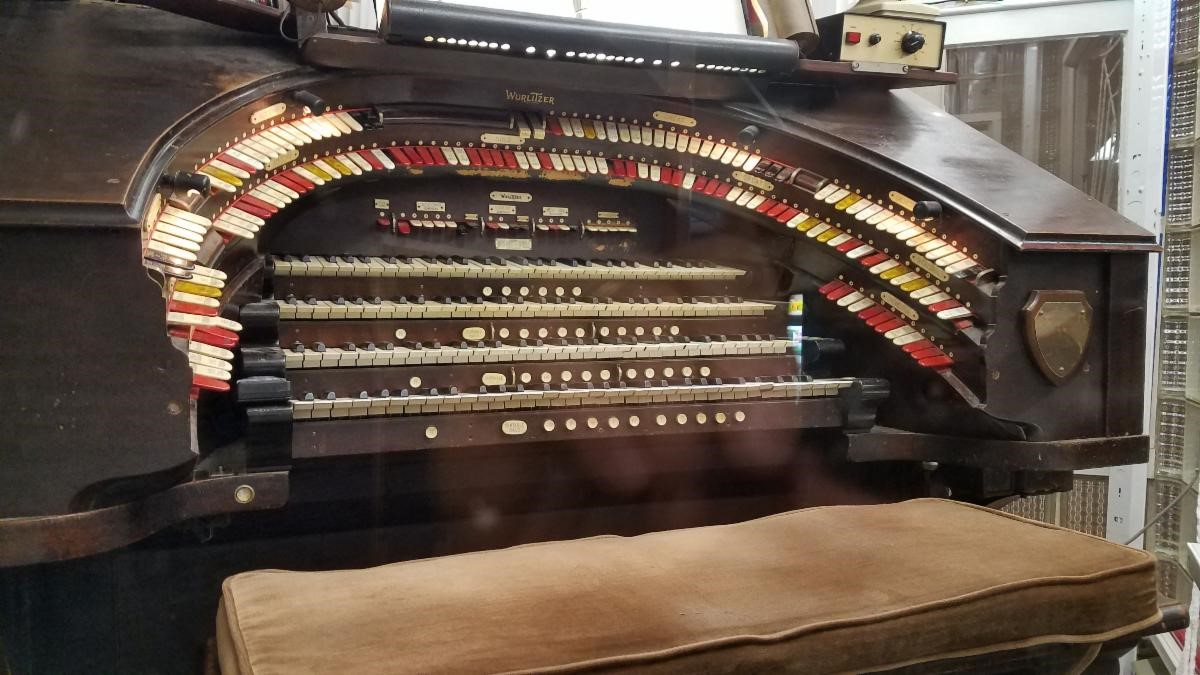

In the Golden Age, the organ was dominant: first the theater pipe organ and later the Hammond Electric Organ. In the late 1920s, “Talkies” movies became common, making the acquisitions of theater pipe organs by roller rinks a bargain. Also, many unemployed organists flocked to the rinks. These were huge machines that required much fine tuning, but they could replicate the sound of the brass band that accompanied roller skaters in skating’s first boom in the 1870s and 1880s.

“. . . the most probable reason for the rink’s return to popular culture was that roller rinks were being outfitted with new pipe organs,” said Poletti. They were popular at that time, having been prominent during the recent silent movie era, and they were highly respectable, being used in many churches. With the invention of the Hammond organ in 1935, a much smaller and simpler instrument began to gain prominence, but it essentially played the same music.

“The controlled tempos of the pipe organs produced a deeply rhythmic form of roller skating,” said Poletti. “Golden Age roller rinks emphasized rhythm inasmuch as the music and movements were in direct dialogue.” All music has tempo and rhythm, but this was a special, symbiotic relationship.

This Wurlitzer theatre pipe organ can still be heard all day Sunday for public skating sessions at the Oaks Park Roller Rink in Portland, Oregon. It has 1500 pipes. It was built in 1926 and installed in The Oaks in 1955. But this wasn’t The Oaks first theatre pipe organ. It 1922, the rink installed a William Wood theatre pipe organ, perhaps the first roller skating rink in the United States with such an organ. During the hard times for roller skating rinks in the 1920s, adopting this new type of instrument and music genre, perhaps played a role in The Oaks surviving the roller skating rinks’ doldrums of the decade, and becoming the oldest continuous operating roller skating rink in the country. The Puget Sound Theatre Organ Society lists 17 roller skating rinks in Washington and Organ states alone that had theatre pipe organs during the Golden Age of roller skating.

This Wurlitzer theatre pipe organ can still be heard all day Sunday for public skating sessions at the Oaks Park Roller Rink in Portland, Oregon. It has 1500 pipes. It was built in 1926 and installed in The Oaks in 1955. But this wasn’t The Oaks first theatre pipe organ. It 1922, the rink installed a William Wood theatre pipe organ, perhaps the first roller skating rink in the United States with such an organ. During the hard times for roller skating rinks in the 1920s, adopting this new type of instrument and music genre, perhaps played a role in The Oaks surviving the roller skating rinks’ doldrums of the decade, and becoming the oldest continuous operating roller skating rink in the country. The Puget Sound Theatre Organ Society lists 17 roller skating rinks in Washington and Organ states alone that had theatre pipe organs during the Golden Age of roller skating.

Pictured is Dominic Cangelosi, museum trustee, with his Hammond B3 organ with Leslie speakers that he not only donated to the museum in 2013, but personally delivered it to the museum from California. He played this organ for USARS Nationals for forty years from 1969 until 2009.

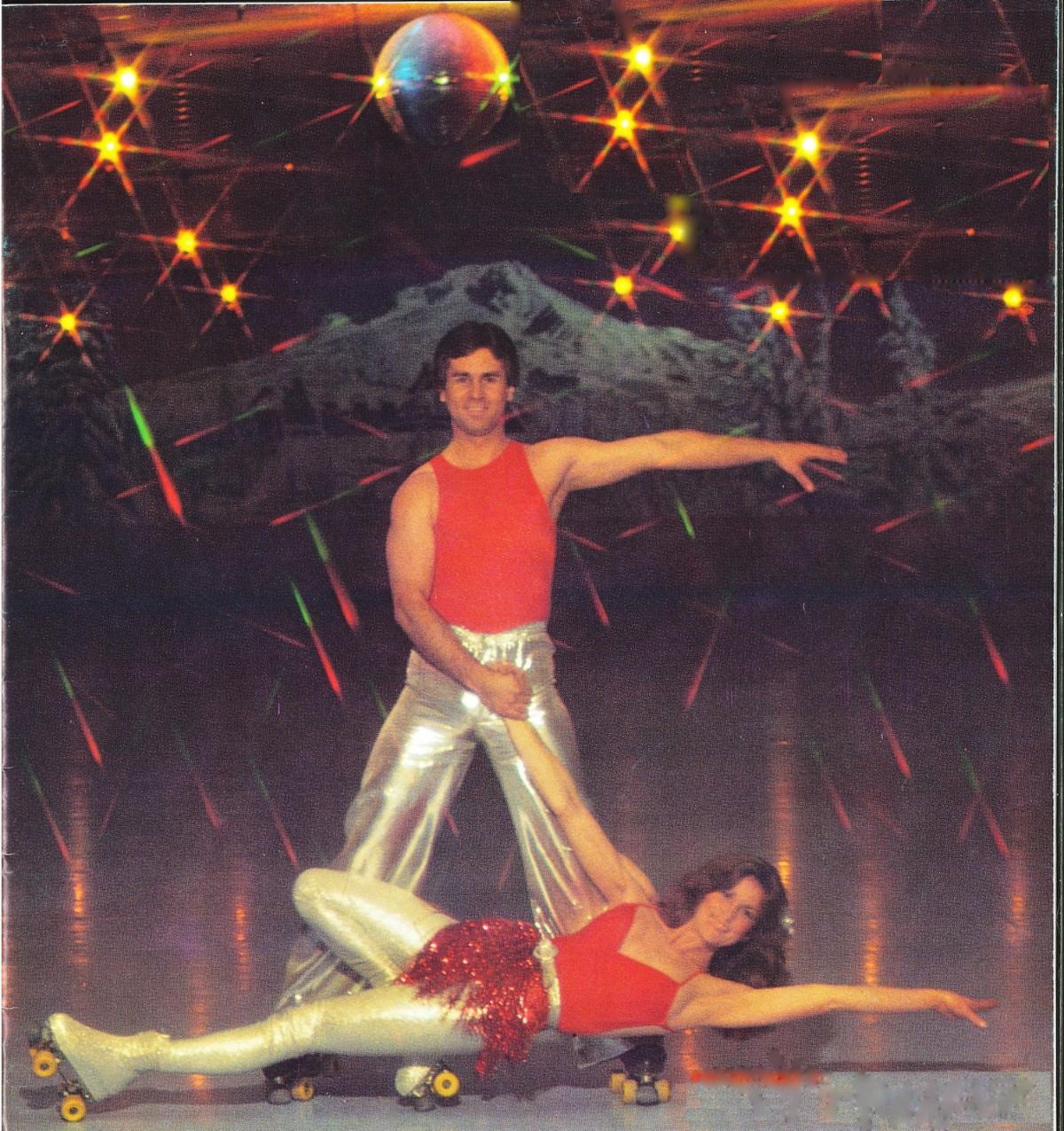

In the Roller Disco era, DJs and vinyl records replaced the organist and the organ. At first glance, this was a radical change. But as Poletti said regarding disco music and roller skating, “This relationship could be attributed to the same features which made organ music ‘natural’ in the rink; its cyclical rhythm and repetition were emulative of the movement on the rink itself.”

In the Roller Disco era, DJs and vinyl records replaced the organist and the organ. At first glance, this was a radical change. But as Poletti said regarding disco music and roller skating, “This relationship could be attributed to the same features which made organ music ‘natural’ in the rink; its cyclical rhythm and repetition were emulative of the movement on the rink itself.”

But herein lies the paradox. “The repetition that is inherent in disco, the feature which made it successful in roller skating, was the precise reason it met with hostile critical reaction,” said Poletti. In other words, rock and roll, and its more spontaneous beat, not only diminished the popularity of waltzes played by organists, but also disco played by DJs. The repetitive sounds of the organist waltz and DJ’s disco that so integrally meshed with the movements and rhythms of roller skating, were discarded by rock and roll enthusiasts. “The rhythm of rock and roll did not coincide with the rhythm of roller skating,” added Poletti.

Today, most rinks use music as a backdrop, similar to the way a soundtrack is used in cinema, as Poletti pointed out. Most skaters today in public skating sessions are not skating/dancing to the music, though there are important exceptions, such as Jam, Shuffle and JB skaters. Though the use of music by most public session skaters may be different today than in the Golden Age and Roller Disco eras, it nevertheless is crucial.

Poletti pointed out the current thinking in cinema studies: the importance of the soundtrack to the cinematic experience. This soundtrack is in the background of the on-screen action, but it’s vitally important. Just like a movie’s soundtrack, the soundtrack played in roller skating rinks is essential to the skating experience. What is played over the sound system may be as important as the skates and the floor. Poletti’s thesis described in academic language what any roller skater knows: the roller-skating experience has always been, and still is, much about the music.

This museum’s Ragtime Band Organ was a great addition to the museum in 2012, supported by grants from the USA Roller Sports Foundation and Ragtime Automated Music. These air powered instruments are activated by paper rolls similar to those of a player piano. Kids love to put a quarter in it, and the museum immediately reverberates with the cacophony of carousel-like music. But what creates excitement with one play, can become somewhat monotonous for today’s ears when played repeatedly.

Though virtually nothing has been written about his topic, perhaps the band organ was one reason for the 1920s being the worst decade for roller rink attendance in the 20th century.

This band organ’s sound may have been popular in the era before WWI, but the 1920s ushered in the Jazz Age and the Charleston, and perhaps young people of that era felt the sounds of the band organ outdated much like the later rock and rollers felt about theatre organs and disco music.

This 1906 Gramophone donated by Robert & Annelle Anderson’s family to the museum, was popular in smaller “parlor skating” rinks in the early 1900s. Little has been written about its use.